I chimici del MIT e della Duke University hanno decuplicato in modo innovativo la forza dei polimeri incorporando legami più deboli nelle loro strutture, una scoperta che non altera le altre proprietà fisiche dei materiali. Questa svolta potrebbe avere un enorme impatto sull’aumento della durata dei pneumatici in gomma e sulla riduzione dei rifiuti di microplastica, tra le altre applicazioni.

Aggiungendo legami deboli a una rete polimerica, i chimici hanno notevolmente migliorato la resistenza del materiale allo strappo.

Un team di chimici del MIT e della Duke University ha scoperto un modo controintuitivo per rendere i polimeri più forti: introducendo alcuni dei legami più deboli nel materiale.

Lavorando con un tipo di polimero noto come elastomero di poliacrilato, i ricercatori hanno scoperto che potevano aumentare la resistenza del materiale allo strappo fino a dieci volte, semplicemente utilizzando un tipo più debole di reticolante per unire alcuni degli elementi costitutivi del polimero.

Questi polimeri simili alla gomma sono comunemente usati nelle parti di automobili e sono anche spesso usati come “inchiostro” per oggetti stampati in 3D. I ricercatori stanno ora esplorando la possibilità di estendere questo approccio ad altri tipi di materiali, come i pneumatici in gomma.

Jeremiah Johnson, professore di chimica a[{” attribute=””>MIT and one of the senior authors of the study, which was published on June 22 in the journal Science.

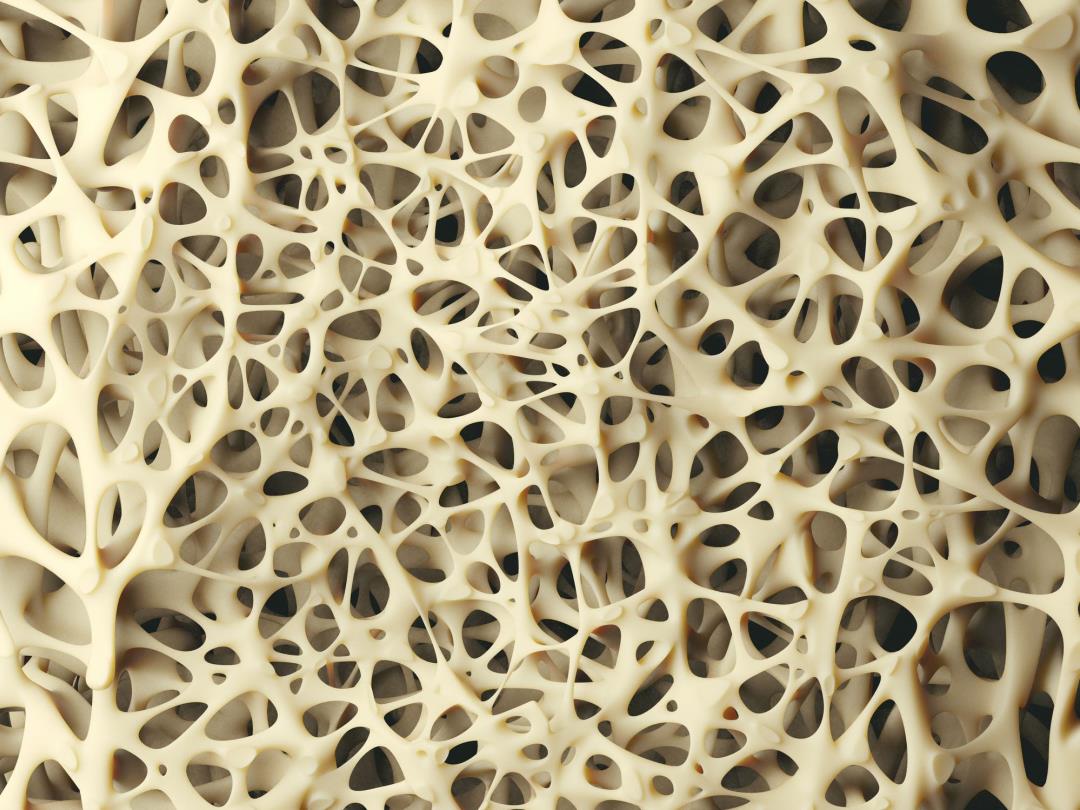

As this polymer network is stretched, weaker crosslinking bonds (blue) break more easily than any of the strong polymer strands, making it more difficult for a crack to propagate through the material. Credit: Courtesy of the researchers, edited by MIT News

A significant advantage of this approach is that it doesn’t appear to alter any of the other physical properties of the polymers.

“Polymer engineers know how to make materials tougher, but it invariably involves changing some other property of the material that you don’t want to change. Here, the toughness enhancement comes without any other significant change in physical properties — at least that we can measure — and it is brought about through the replacement of only a small fraction of the overall material,” says Stephen Craig, a professor of chemistry at Duke University who is also a senior author of the paper.

This project grew out of a longstanding collaboration between Johnson, Craig, and Duke University Professor Michael Rubinstein, who is also a senior author of the paper. The paper’s lead author is Shu Wang, an MIT postdoc who earned his PhD at Duke.

The weakest link

Polyacrylate elastomers are polymer networks made from strands of acrylate held together by linking molecules. These building blocks can be joined together in different ways to create materials with different properties.

One architecture often used for these polymers is a star polymer network. These polymers are made from two types of building blocks: one, a star with four identical arms, and the other a chain that acts as a linker. These linkers bind to the end of each arm of the stars, creating a network that resembles a volleyball net.

In a 2021 study, Craig, Rubinstein, and MIT Professor Bradley Olsen teamed up to measure the strength of these polymers. As they expected, they found that when weaker end-linkers were used to hold the polymer strands together, the material became weaker. Those weaker linkers, which contain cyclic molecules known as cyclobutane, can be broken with much less force than the linkers that are usually used to join these building blocks.

As a follow-up to that study, the researchers decided to investigate a different type of polymer network in which polymer strands are cross-linked to other strands in random locations, instead of being joined at the ends.

This time, when the researchers used weaker linkers to join the acrylate building blocks together, they found that the material became much more resistant to tearing.

This occurs, the researchers believe, because the weaker bonds are randomly distributed as junctions between otherwise strong strands throughout the material, instead of being part of the ultimate strands themselves. When this material is stretched to the breaking point, any cracks propagating through the material try to avoid the stronger bonds and go through the weaker bonds instead. This means the crack has to break more bonds than it would if all of the bonds were the same strength.

“Even though those bonds are weaker, more of them end up needing to be broken, because the crack takes a path through the weakest bonds, which ends up being a longer path,” Johnson says.

Tough materials

Using this approach, the researchers showed that polyacrylates that incorporated some weaker linkers were nine to 10 times harder to tear than polyacrylates made with stronger crosslinking molecules. This effect was achieved even when the weak crosslinkers made up only about 2 percent of the overall composition of the material.

The researchers also showed that this altered composition did not alter any of the other properties of the material, such as resistance to breaking down when heated.

“For two materials to have the same structure and same properties at the network level, but have an almost order of magnitude difference in tearing, is quite rare,” Johnson says.

The researchers are now investigating whether this approach could be used to improve the toughness of other materials, including rubber.

“There’s a lot to explore here about what level of enhancement can be gained in other types of materials and how best to take advantage of it,” Craig says.

Reference: “Facile mechanochemical cycloreversion of polymer cross-linkers enhances tear resistance” by Shu Wang, Yixin Hu, Tatiana B. Kouznetsova, Liel Sapir, Danyang Chen, Abraham Herzog-Arbeitman, Jeremiah A. Johnson, Michael Rubinstein and Stephen L. Craig, 22 June 2023, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.adg3229

The group’s work on polymer strength is part of a National Science Foundation-funded center called the Center for the Chemistry of Molecularly Optimized Networks. The mission of this center, directed by Craig, is to study how the properties of the molecular components of polymer networks affect the physical behavior of the networks.

“Appassionato pioniere della birra. Alcolico inguaribile. Geek del bacon. Drogato generale del web.”