Spinosaurus, il dinosauro predatore più lungo conosciuto, apre le sue mascelle allungate, tempestate di denti conici, per catturare la sega. Contrariamente ai suggerimenti precedenti, questo animale non era un airone trampoliere: era una “bestia fluviale”, che inseguiva attivamente la preda in un vasto sistema fluviale situato nel moderno Nord Africa. Le ossa dense nello scheletro dello Spinosaurus suggeriscono fortemente che abbia trascorso molto tempo immerso nell’acqua. Credito: David Bonadonna

Anche il suo cugino Baryonyx potrebbe aver nuotato, ma Suchomimus potrebbe aver guadato come un airone.

Spinosauro È il più grande dinosauro carnivoro mai scoperto, più grande di T-Rex—Ma il metodo per catturarli è oggetto di dibattito da decenni. È difficile intuire il comportamento di un animale che conosciamo solo dai fossili; Sulla base del suo scheletro, alcuni studiosi lo hanno suggerito Spinosauro Sa nuotare, ma altri credono che abbia guadato nell’acqua come un airone. Dal momento che guardare l’anatomia dei dinosauri spinosauridi non è stato sufficiente per risolvere il mistero, un gruppo di paleontologi sta pubblicando un nuovo studio in natura Adotta un approccio diverso: controllando la loro densità ossea. Analizzando la densità ossea degli spinosauri e confrontandoli con altri animali come pinguini, ippopotami e coccodrilli, il team ha scoperto che Spinosauro e i suoi parenti Barionice Avevano ossa dense che probabilmente permettevano loro di immergersi sott’acqua per la caccia. Nel frattempo, un altro dinosauro imparentato ha chiamato Schomemo Le sue ossa erano più leggere, il che avrebbe reso più difficile il nuoto, quindi probabilmente guaderà o trascorrerà più tempo a terra come gli altri dinosauri.

Baryonyx, del Surrey in Inghilterra, nuota attraverso un antico fiume con un pesce nella mascella. Come il suo più grande parente africano Spinosaurus, Baryonyx aveva ossa dense, indicando che trascorreva anche gran parte del suo tempo immerso nell’acqua. In precedenza si pensava che fosse meno acquatico del suo parente del deserto. Credito: David Bonadonna

afferma Matteo Fabri, ricercatore post-dottorato al Field Museum e autore principale del libro di studio natura. “Altri studi si sono concentrati sull’interpretazione dell’anatomia, ma è chiaro che se ci sono interpretazioni opposte riguardo alle stesse ossa, questa è già una chiara indicazione che questi probabilmente non sono i nostri migliori proxy per dedurre l’ecologia degli animali estinti”.

Tutta la vita inizialmente proveniva dall’acqua e la maggior parte dei gruppi di vertebrati terrestri ha organi a loro volta – ad esempio, mentre la maggior parte dei mammiferi vive sulla terraferma, abbiamo balene e foche che vivono nell’oceano e altri mammiferi come lontre, tapiri e semi -ippopotami acquatici. Gli uccelli hanno pinguini e cormorani. I rettili includono coccodrilli, coccodrilli, iguane marine e serpenti marini. Per molto tempo, i dinosauri non aviari (dinosauri che non si sono trasformati in uccelli) sono stati l’unico gruppo che non aveva abitanti dell’acqua. Ciò è cambiato nel 2014, quando un file Spinosauro Lo scheletro descritto da Nizar Ibrahim in[{” attribute=””>University of Portsmouth.

Scientists already knew that spinosaurids spent some time by water—their long, croc-like jaws and cone-shaped teeth are similar to other aquatic predators’, and some fossils had been found with bellies full of fish. But the new Spinosaurus specimen described in 2014 had retracted nostrils, short hind legs, paddle-like feet, and a fin-like tail: all signs that pointed to an aquatic lifestyle. But researchers have continued to debate whether spinosaurids actually swam for their food or if they just stood in the shallows and dipped their heads in to snap up prey. This continued back-and-forth led Fabbri and his colleagues to try to find another way to solve the problem.

“The idea for our study was, okay, clearly we can interpret the fossil data in different ways. But what about the general physical laws?” says Fabbri. “There are certain laws that are applicable to any organism on this planet. One of these laws regards density and the capability of submerging into water.”

Simone Maganuco (middle), Davide Bonadonna (right) and lead author Matteo Fabbri (left) organizing fossils at night. Credit: Nanni Fontana

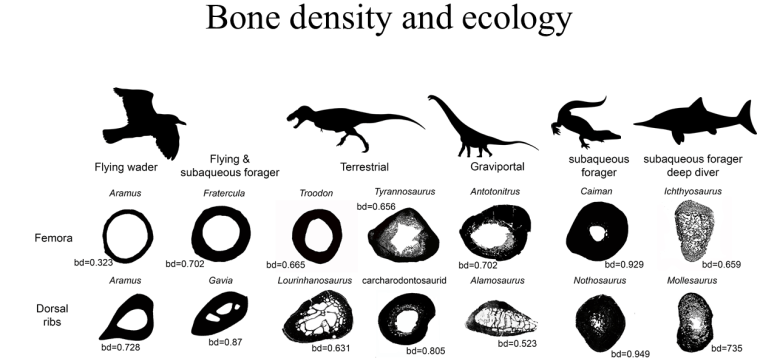

Across the animal kingdom, bone density is a tell in terms of whether that animal is able to sink beneath the surface and swim. “Previous studies have shown that mammals adapted to water have dense, compact bone in their postcranial skeletons,” says Fabbri. Dense bone works as buoyancy control and allows the animal to submerge itself.

“We thought, okay, maybe this is the proxy we can use to determine if spinosaurids were actually aquatic,” says Fabbri.

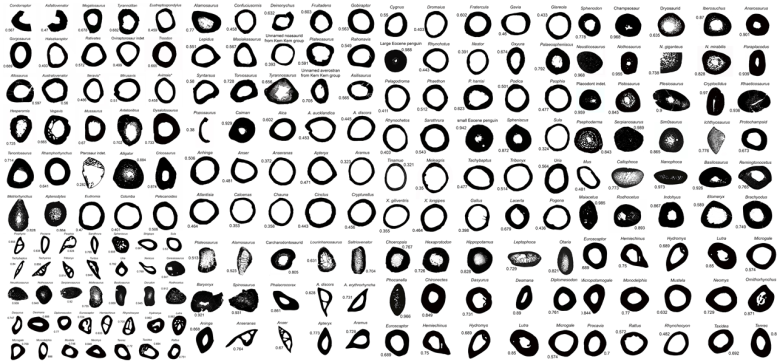

Fabbri and his colleagues, including co-corresponding authors Guillermo Navalón at Cambridge University and Roger Benson at Oxford University, put together a dataset of femur and rib bone cross-sections from 250 species of extinct and living animals, both land-dwellers and water-dwellers. The researchers compared these cross-sections to cross-sections of bone from Spinosaurus and its relatives Baryonyx and Suchomimus. “We had to divide this study into successive steps,” says Fabbri. “The first one was to understand if there is actually a universal correlation between bone density and ecology. And the second one was to infer ecological adaptations in extinct taxa” Essentially, the team had to show a proof of concept among animals that are still alive that we know for sure are aquatic or not, and then applied them to extinct animals that we can’t observe.

When selecting animals to include in the study, the researchers cast a wide net. “We were looking for extreme diversity,” says Fabbri. “We included seals, whales, elephants, mice, hummingbirds. We have dinosaurs of different sizes, extinct marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. We have animals that weigh several tons, and animals that are just a few grams. The spread is very big.”

This menagerie of animals revealed a clear link between bone density and aquatic foraging behavior: animals that submerge themselves underwater to find food have bones that are almost completely solid throughout, whereas cross-sections of land-dwellers’ bones look more like donuts, with hollow centers. “There is a very strong correlation, and the best explanatory model that we found was in the correlation between bone density and sub-aqueous foraging. This means that all the animals that have the behavior where they are fully submerged have these dense bones, and that was the great news,” says Fabbri.

When the researchers applied spinosaurid dinosaur bones to this paradigm, they found that Spinosaurus and Baryonyx both had the sort of dense bone associated with full submersion. Meanwhile, the closely related Suchomimus had hollower bones. It still lived by water and ate fish, as evidenced by its crocodile-mimic snout and conical teeth, but based on its bone density, it wasn’t actually swimming.

Other dinosaurs, like the giant long-necked sauropods also had dense bones, but the researchers don’t think that meant they were swimming. “Very heavy animals like elephants and rhinos, and like the sauropod dinosaurs, have very dense limb bones, because there’s so much stress on the limbs,” explains Fabbri. “That being said, the other bones are pretty lightweight. That’s why it was important for us to look at a variety of bones from each of the animals in the study.” And while there are limitations to this kind of analysis, Fabbri is excited by the potential for this study to tell us about how dinosaurs lived.

“One of the big surprises from this study was how rare underwater foraging was for dinosaurs, and that even among spinosaurids, their behavior was much more diverse that we’d thought,” says Fabbri.

Jingmai O’Connor, a curator at the Field Museum and co-author of this study, says that collaborative studies like this one that draw from hundreds of specimens, are “the future of paleontology. They’re very time-consuming to do, but they let scientists shed light onto big patterns, rather than making qualitative observations based on one fossil. It’s really awesome that Matteo was able to pull this together, and it requires a lot of patience.”

Fabbri also notes that the study shows how much information can be gleaned from incomplete specimens. “The good news with this study is that now we can move on from the paradigm where you need to know as much as you can about the anatomy of a dinosaur to know about its ecology, because we show that there are other reliable proxies that you can use. If you have a new species of dinosaur and you just have only a few bones of it, you can create a dataset to calculate bone density, and at least you can infer if it was aquatic or not.”

Reference: “Subaqueous foraging among carnivorous dinosaurs” by Matteo Fabbri, Guillermo Navalón, Roger B. J. Benson, Diego Pol, Jingmai O’Connor, Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, Gregory M. Erickson, Mark A. Norell, Andrew Orkney, Matthew C. Lamanna, Samir Zouhri, Justine Becker, Amanda Emke, Cristiano Dal Sasso, Gabriele Bindellini, Simone Maganuco, Marco Auditore and Nizar Ibrahim, 23 March 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04528-0

“Appassionato pioniere della birra. Alcolico inguaribile. Geek del bacon. Drogato generale del web.”